I ordered ugly shoes. The Adidas Taekwondo Mei Ballet Flats, specifically. I love them. I unboxed and tried them on immediately, still in pajamas. I walked around my apartment, looked in the mirror, popped my leg out behind me. Pleased, I flopped into bed and kicked my feet up like a teenage girl, crossing them at the ankle— my chin in my hands, a fluffy pink gel pen practically materializing behind my ear. A lock of hair came loose and fell in front of my eyes, demanding to be twirled. All I needed was a Lisa Frank journal to write my crush’s name in 100 times.

The shoes were the first unnecessary clothing purchase in months. I savored my new identity in them: energized, youthful, imaginative.

There is something wonderfully ungovernable about wearing clothes that aren’t universally attractive. A certain power exists knowing they’re not for everyone— and that you are dressing for no one’s gaze but your own. I felt uninspired trying to rework the same outfits over and over. These ballet-flats-meet-sneakers lent me a new perspective to consider unexpected— maybe uglier— combinations: clashing patterns, mixed styles, textures, and proportions, old pieces I’d sworn off. More than defiance, I felt a sort of rebirth knowing the person wearing these wasn’t the same one who felt stuck.

I could have bought Sambas. Would they have catapulted me out of my rut in the same way? I’d like to think not. A small rebellion, but recently I’ve found myself gravitating towards Ugly Things.

(Let me hedge that statement— some ugly things are senseless and evil; I am not talking about those. I am talking about shoes).

I feel towards ugliness how a rubbernecker feels towards a car crash: a deviant fascination and an inability to look away. Ugliness seems more substantive than beauty, frankly. I’m not the first to think this. See: punks, feminists, activists, Julia Fox, to name a few.

Questions began to percolate: Why is something ugly? Could it be beautiful? Does ugly equal bad? Or does ugly equal challenging? Who decides?

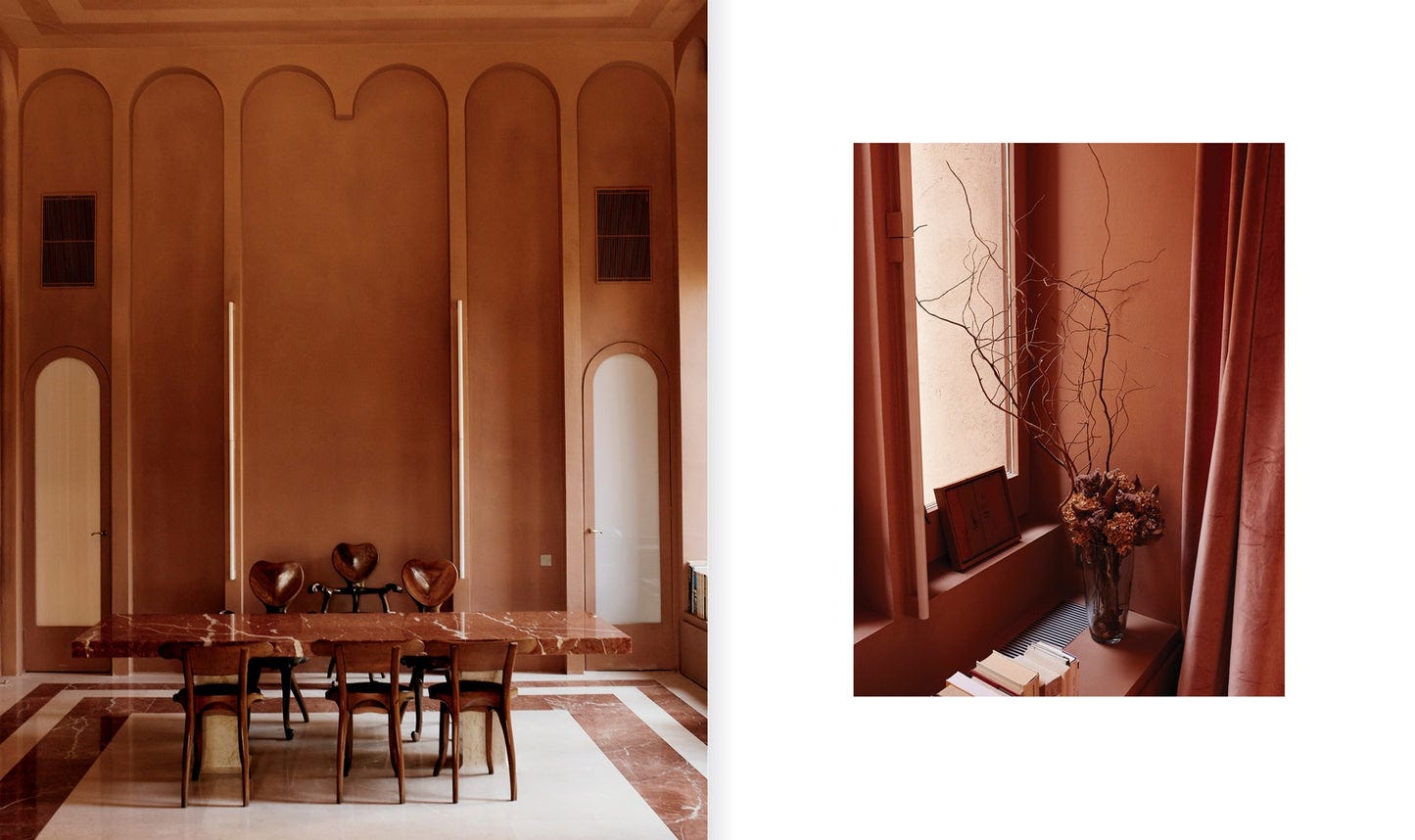

In La Fábrica

Once enthralled with the potential of ugliness, you start to see it everywhere.

I recently stumbled upon photos online of an architectural project outside Barcelona called La Fábrica. The brainchild of late Spanish architect, Ricardo Bofill, La Fábrica stands today as the headquarters for his architecture firm, Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura. Originally, it also functioned as a home for him and his family. The structure is a 1920s cement factory, once set to cease production and remain abandoned, that Bofill started restoring in 1973. One might think, who would look at the ruins of a cement factory and want to live there?

Turns out, Bofill’s vision was magnificent.

Rather than being designed, the space was almost sculpted. Like a sculpture, the excess was removed and the openings and voids were carved out. It took three years to complete, or rather, to allow it to be occupied, because, as we have said, it has never been completely finished. It continues to pulse. - Domus

The cement factory before:

La Fábrica after:

RBTA’s website details the thought and philosophy behind the project:

Looking through the concrete flesh of the vast complex, it was possible to look beyond the designated function of the cement factory, and unearth its new life.

Various forms and shapes became visible... The factory was a gem of mixed architectural trends from the past:

Surrealism in stairs leading to nowhere and elements hanging over voids, as well as visually powerful spaces of weird proportions;

Abstraction in the pure volumes, at times revealing themselves broken and raw;

Brutalism in the crude, concrete materiality of the place.

The contradictions and the ambiguity of the complex inherently hinted at a rebirth. They were not dictating its purpose anymore. The process Ricardo Bofill embarked on was, chiefly, a theoretical rethinking of the relationship between space and function. The use may, indeed, fit the space. By rejecting the original functionalist approach of the structure as a cement factory, La Fábrica was now unravelling its allure. From an industrial settlement in decay, the skillful architect could carve a place where work and life fulfill themselves in a virtuous continuum.

Bofill saw through the ugliness and ruin of industry, to create a space eerily captivating. La Fábrica also stands as a rejection of the status quo, announcing loudly that reclamation, reuse, and prudent design have power. The silos remain tall and challenging: a thumbing of the nose at the ruling class’s definition of art, luxury, and beauty.

What was once a grey, polluting behemoth dominated by cement has been transformed into a leafy Mediterranean orchard with palm, olive and eucalyptus trees. The walls have gradually been covered by trailing ivy, concealing them almost entirely. “The approach taken was very minimalistic, very simple, using cheap materials. I don’t like my designs to look luxurious. Luxury comes from your lifestyle, from the space itself. It’s not about using expensive materials. I’ve never liked the houses traditionally preferred by the petty bourgeoisie.” - Domus

In the Weeds

Back in my own life, I was getting a martini with a friend after work. Off the cuff, they said, “I don’t know how to tell you this, but your writing has an undercurrent of boredom.”

Oh, god, I thought. My throat tightened. Never mind I struggled to write that day, and the weeks prior, beginning and deleting multiple drafts. Well sock me in the stomach and consider me humbled—

“I don’t mean it negatively,” he elaborated, “I think everyone goes through eras and you’re in the boredom phase. You need to level up and be bad at something.”

To add insult to injury, I was coming off a shift where we got absolutely rocked. I felt I was bad at plenty of things. My writing was ugly, our service was ugly, everything was ugly.

The next day I discussed being “in the weeds” (struggling to keep up with a large amount of responsibilities during the previous night) with a mentor. Him: “I don’t feel bad about it, necessarily. A friend once told me they could not always protect their child from people being mean. This is like that. I think it was a necessary moment of growth for the team.”

That night, service went smoother. We knew the challenges and rose to them.

Similarly, I started the draft for this essay. Maybe I needed to write something ugly to eventually produce something better. Maybe I needed to get over it, and kill my ego. I decided to write, literally, about ugliness.

In Conclusion

Turns out, there is a richness to Ugly. A hearty meat to sink your teeth into. Questioning ugliness in the world (and yourself) is important because it is a well from which many things can spring— among them rebirth, growth, imagination, innovation, and beauty. What a shame to write something off because it is ugly.

And, side-note: I can skip around as easily in the taekwondo flats as I can in sambas. There is a delightful freedom in that.

Kate when I tell you I have sent these exact shoes to people and asked "are these nuts?" and now I wish I got them.

I opted for the regular black taekwoendo ones sans laces and left them in Spain so now I bought more basic adidas literally yest but at least they are from the Japan line...

HERE'S 2 UGLY