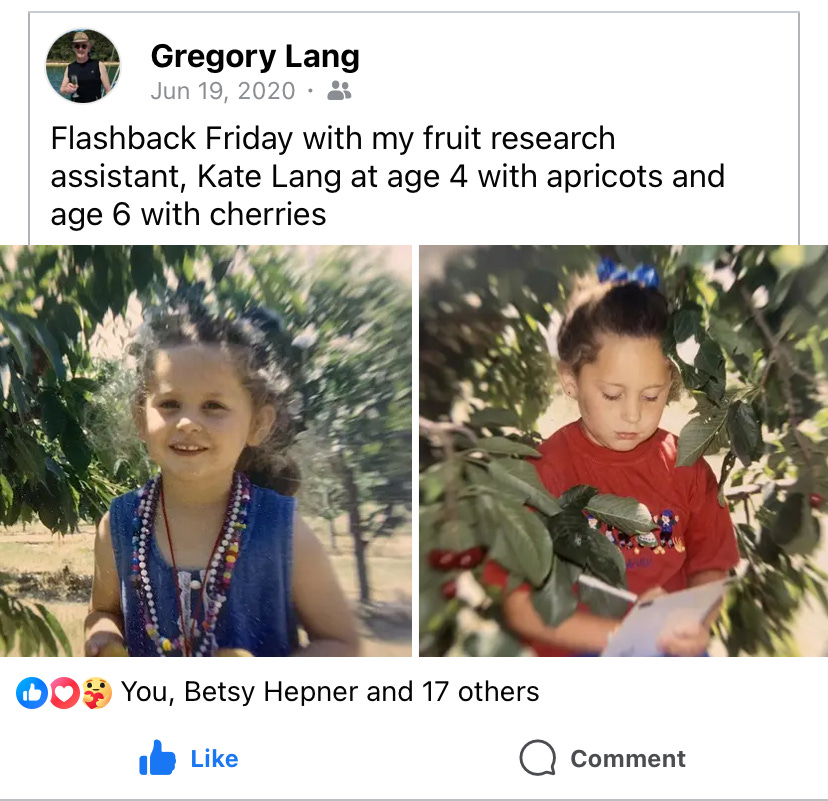

My father is a cherry expert. Or, Cherry Scientist. Or, Professor at Michigan State— when people ask.

Every year growing up, a refrigerator in our basement routinely filled with bags of sweet cherries— each labeled carefully in sharpie. When friends visited during the dog days of summer, we retreated to the cold basement and rollerbladed on the unfinished concrete floors. Eventually, the friend would get hungry and open the refrigerator looking for snacks. Their eyes widened. They looked at me with concern.

It’s a funny sight when you’re not expecting it— a fridge full of cherries. Like a strange episode of MTV cribs.

“Can I have some?”

“Yeah, but don’t eat from that bag— those are experiment cherries.”

“Experiment cherries?” Escalated concern. It wasn’t a Frankenstein-style experiment, I explained. The cherries weren’t radioactive. My dad was probably testing cross pollination, trellising systems, or different rootstocks. This information was lost on my friends.

“They’re safe,” I promised.

It was a niche childhood.

My mother (retired) also worked in the Horticulture Department at Michigan State. She worked at a winery too, when I was really little. For a long time, I distanced myself from their professions. My friends at school couldn’t relate and I felt like an alien. Cue the cherry fridge. My parents discussed their research over glasses of wine at dinner. I tuned out their conversations and told them I HATED wine. I was preoccupied with Avril Lavigne and dying my hair purple. I’m going to be nothing like them, I told myself. Don’t all children recite a version of this?

During my sophomore year of college, I got two part-time jobs: one in the school’s garden and one in the viticulture lab. Somehow I found myself closer to my parents’ interests than ever. I planted, watered, and mulched. I clicked through pictures of budding grape clusters on a desktop computer, counting and recording the numbers. I measured the surface area of grape leaves. I had no idea what this proved. Real grunt-work. I was bored and figuring myself out: I liked gardening, disliked the lab, and still hated wine. If nothing else, these jobs provided a lens through which to begin reexamining my upbringing.

Some background on my dad: his father was an engineer who liked to garden. My grandfather taught my father to grow plants, which led him to pursue horticulture. My dad moved to UC Davis for grad school.

In 2018, I packed up and headed to California myself— a move that mirrored my father’s. I was there, ironically, to study wine and work in a tasting room— a job that mirrored my mother’s. Despite my best efforts, I was turning out like them.

As I grew up and traveled further from home, I kept finding myself returning in a way. I saw my family in a new light, and understood them in ways one only can as an adult. It’s strange to meet your parents part way through their lives. Stranger yet to meet your grandparents in the autumn and winter of their lives. For so long, I took their roles for granted. “Mom,” “Dad,” “Grandpa.” I failed to consider them as fully formed people. Although we are still markedly different, I feel the fabric of our lives weaving together as the years pass. My grandpa’s love of gardening led to my father’s career, which led him to California, to cherries, to meeting my mom, to me, to Washington State and then Michigan, to teaching a Wine Class at MSU. I grew up in Washington State, by Michigan, moving away to Chicago and then California, to wine country, and eventually back to the Midwest where I recently gave a guest lecture in my father’s Wine Class. A real full circle moment.

And these moments keep occurring with greater frequency.

Every night, I pour wine for guests at work. But it’s not just me and the guests; my parents are there at the dinner table, talking about their research. My grandpa is out in his garden, sharing his knowledge and love of plants. My ancestry continues to live on as my own path unfolds. Rather than fighting this, like I did as a child, I now feel a wonderful sense of discovery— of coming home. The crafts of my parents and grandparents are my crafts. I will always get to share that with them.

Every summer I buy bags of cherries at the farmer’s market, and every year they taste a little sweeter.

Jim! So much of my childhood spent watching him garden. He buried our dogs back there and marked their graves with rocks. I hope that sounds sweet like I mean it instead of morbid.

Funny how we hit a certain point in our lives and our bones remember what they've always known. I resisted textile arts for a long time, I found them stuffy and didn't see the point. But I'm a year into quilting, learning how to sew clothes and wanting to make my own dyes. My Finnish Great Grandmother could do it all, with a love and skill for rugs and latch hook. I understand now at 32, why she kept her hands busy. And I feel that much more understanding and closeness to someone who our lives only overlapped by 3 years.